Introduction | Codicological description | Content | Authors | References | Appendix

Introduction

The Ms. Marshall 29 is held in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. In all probability, Thomas Marshall, rector of Lincoln College in Oxford, acquired the manuscript while he was in the Netherlands as a vicar in the years 1647-1672 (Deschamps 1972:119). The parchment manuscript is complete, comprising of 102 folios in 13 gatherings. According to Kienhorst (2005:799), the text in littera textualis in two columns of 49 lines each, is written by one hand. However, we have discovered that the text is written in two hands, although barely distinguishable (f.1r-68r and 68v-102v). Carefully comparing line initial capitals, we find that various letters including D, H, L and W are differently shaped from f.68v onwards. This change is sudden and takes place in the middle of Book III and each individual hand is consistent. We follow Kienhorst in dating the manuscript around 1375. A codicological description, an overview of the content and the authors of the various texts as well as a bibliography, are given below.

Codicological description

The manuscript is written on parchment, i+102 leaves, in two columns, modern folio numbering in pencil, 49 lines per column. The leaves measure 26x17.5cm. The binding is contemporary stamped brown leather on wooden boards, one of the two brass clasps is missing. The spine is restored.

The Summary Catalogue 5264 (Bodleian Library) provides a brief description of the manuscript. The text was previously published in a critical edition by F.A. Snellaert in Nederlandsche Gedichten. (Snellaert, 1869)

The manuscript was compiled as a codicological unity. Each of the four Books begins on the first folio of a new gathering; however, the tables of contents are written on the last folio of the previous gathering. This shows that the gatherings had not been circulated separately before binding, but were intended to be bound together in gatherings of 8 folios. Also, the manuscript is written by two hands, the second hand beginning in the middle of the 9th gathering, which is the middle of Book III. f.1r-68r is from the first hand and f.68v-102v from the second. The rubrication is consistent throughout the manuscript, hence from one hand.

On f.i: (owner’s notation) Dit bouck behoert meester

Yoert borxhoren

| 1st gathering | f.i-7v, flysheet inserted. (f.1r+v table of contents Book I; f.1b column b: start Book I) |

| 2nd gathering | f.8-15 |

| 3rd gathering | f.16-23 (23r+v table of contents Book II) |

| 4th gathering | f.24-31 (f.24r start Book II) |

| 5th gathering | f.32-39 |

| 6th gathering | f.40-47 (f.47r+v table of contents Book III) |

| 7th gathering | f.48-55 (f.48r start Book III) |

| 8th gathering | f.56-63 |

| 9th gathering | f. 64-71 |

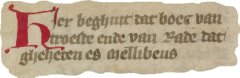

| 10th gathering | f.72-79 (79r blank) (f.79v (in rubrics) Hier beghint dat vierde boecke + incomplete table of contents) |

| 11th gathering | f.80-87 (f.80r start Book IV) |

| 12th gathering | f.88-95 |

| 13th gathering | f.96-102 |

Content

Ms. Marshall 29 contains the following four books from different authors.

- Mellibeus het boec van troeste (by Jan van Boendale) is a didactic poem based on Liber consolationis et consilii by Albertanus van Brescia and completed in 1342. It is written as a dialogue between Melibeus and his wife Prudentia about a moral way of life.

- Jans Teesteye (by Jan van Boendale) is a dialogue between Jan (van Boendale) and his friend Wouter about moral decline in society. This book can be dated between 1330-1334 (Van Anrooij 2002a, 13).

- Boec vander wraken (by Jan van Boendale) is concerned about God’s wrath in the world. Boendale explains historical events as punishment from God. Part one gives examples of wrath from the bible, from lives of priest, prelates and governors and ends with the predictions of the eight sybilles, based on Sibylla Tiburtina. Part two is based on Revelationes Methodii. Boendale demonstrates the bad influence of governors (‘landsheren’) from Noah and Alexander the Great to king Philip VI of France who fought against Edward III of England, which must be the battle of Crézy in 1346. All of the wars that are described, hasten the coming of the anti-christ.Part III is mainly historical, about the role of individuals in wrath and punishment. The last chapters of Part III (3.50-3.53) are based on the 6th version of Brabantsche Yeesten which was completed in 1351.Van Anrooij concludes that Boec vander wraken was written in two versions, the first of which was finished in 1346 and the second version as found in our manuscript in 1351 so the date of 1352 found in our manuscript cannot be correct.In the epilogue we find that Boec vander wraken is dedicated to Jan (III), Duke of Brabant.

- This book contains various texts by different authors.

- In Dit es van Maskeroen (by Van Velthem, cf. Besamusca et al. 2009, 12-13). Maskeroen, representing the devil, tries to resist God’s plan to save humanity but Mary intervenes. Maskeroen is based on the Latin Processus Satanae. (Kestemont 2013, 204).

- In Van den coninc Saladijn ende van Hughen van Tabaryen (by Hein van Aken), from French Ordène de chevalerie, par Huc de Tabarie, the captured crusader Hughe van Tabaryen appears in front of King Saladijn and makes him a knight, thus securing his release. This ‘sproke’ or tale by Hein van Aken perhaps goes back to the late 13th century. It cannot be younger than Jan van Boendale’s Der leken spieghel (1325-1330) since Van Aken’s death is mentioned in this work. It describes a dialogue between the crusader Hughe and the sultan Saladijn. First it relates how Hughe became a captive, then there is the dialogue in which Saladijn asks Hughe about knighthood, what makes a good knight and how to become a knight (Van Anrooij 2002b, 76). Since only a free man can grant knightood, Hughe is released so that he can make king Saladijn a knight. At the end of Book IV there are some lines about how Saladijn fared since, and how he died. These lines do not appear in the Comburg ms., which is the only other manuscript where the text survived, albeit in a Flemish version.

- Die tien plaghen ende die 10 gheboden, the ten plagues and the ten commendments, and Dit is noch van salladine, concerning King Saladijn’s death.

Authors

Jan van Boendale

Jan van Boendale (1279-1351), also known as Jan de Clerc after his profession of city clerk, makes himself known in the prologue to Jans Teesteye.

Alle die ghene die dit werc

Sien lesen ende horen

Die gruetic Jan gheheten clerc

Vander vueren gheboren

Boendale heetmen mi daer

Ende wone tandwerpen nv

Daer ic ghescreuen hebbe menech jaer

Der scepenen brieue dat seggic v[1]

(Book II, paragraph 2.1)

Born in Tervuren, not far from Antwerp, probably in 1279, he spent most of his life in Antwerp where he was a clerk of the city magistrates and in between the pressures of his professional life, he found some time to write literary works (Van Anrooij 2002a, 12). Although no author is mentioned in Boec vander wraken, the book is dedicated to Jan (Jan III), Duke of Brabant, in whose service the author was employed.

Want ict tot hier heb besuyrt

In eren eens goeds mans ende vermoghen

Van brabant des hertoghen

Jans die ic altoos sculdich

Te dienen gheweest menichfuldich

Dit boecsken wilic hem laten[2]

(Book III, epilogue)

Equally, in Melibeus no author is mentioned. This work is also dedicated to the authors’ master the Duke of Brabant as appears from the prologue

Dat ic gherne gheuen soude

Op dats mi god onnen woude

Minen lieuen here den hertoghe

Van brabant dien god verhoghe

Beyde aen ziele ende liue

Want al dat ic hier scriue

Dats troest ende raet wtuercoren

Die den lants here toe behoren[3]

(Book I, prologue)

and the author lived in Antwerp

Al tandwerpen daer ic wone

Maecte ic dit boexken scone[4]

(Book I, prologue)

Also in Boec vander wraken, the author refers to Antwerp as his base, e.g.

Ic hoorde tantwerpen daer ic sat[5]

(Book III, paragraph 3.51)

In the 20th century researchers have shown reluctance to attribute these texts to Jan van Boendale and have therefore introduced the term ‘Antwerpse School’, to indicate that Jan van Boendale may not have been the only author in Antwerp in the first half of the 14th century. However, J.Reynaert convincingly demonstrated that all of these books can be attributed to Jan van Boendale. He consequently no longer adheres to the notion of the ‘Antwerp School’ (Reynaert 2002). Kestemont’s computer based stylometric analyses confirm that Melibeus and Boec vander wraken were written by Jan van Boendale (Kestemont forthc., 199-200). In the light of these convincing results, we will also assume that Melibeus and Boec vander wraken were written by Jan van Boendale. For a list of Boendale’s texts, see Appendix.

Hein van Aken

Hein van Aken (ca.1250-1330) is the author of Saladijn in book IV as appears in the last sentence of this text

Dit heeft ghedicht te loue ende teren

Allen riddren . heyne van aken.

(Book IV, paragraph 4.02)

Saladijn is the only work that can be attributed with certainty to this author. Hailing from Brussels, Hein van Aken is a Brabant author like Jan van Boendale. Jan van Boendale knew him, he even remembers two verses from Hein van Aken in his Lekenspiegel

Van Bruecele Heine van Aken

Die wel dichte conste maken

God hebbe die ziele sine

Maecte dese twee versekine

Vrient die werdet langhe ghesocht

Selden vonden ende saen verwrocht

(De Vries 1844–1848, 183 boek iii, kap. 17, vs. 91-96)

It has been suggested that both authors attended the capittelschool in Brussels.

Lodewijk van Velthem

A contemporary of Jan van Boendale, Lodewijk van Velthem worked in Zwichem (near Leuven) before being appointed in Veltem-Beisem. He states in Spieghel Historiael that he comes from Brabant. Van Velthem finished the fourth part (Vierde Partie) of Jacob van Maerlant’s Spieghel Historiael in 1315. The Maskeroen text which he used in the Vierde Partie he then integrated in Jacob van Maerlant’s Boec van Merline. (Besamusca et al 2009, 12-15). Since Van Velthem integrated this text into Van Maerlants work, he is possibly the one who reworked the latin text into Middle Dutch and may be regarded as the author of Maskeroen.

The authors of the various texts hail from Brabant. Jan van Boendale (1279 – 1351) was a clerk in Antwerp; his contemporary, Lodewijk van Velthem, worked in Zwichem and in Velthem and the author of Saladijn Hein van Aken (ca.1250-1330) was born in Brussels. Thus, one can assume that their original dialect was that of Brabant, and the manuscript as a whole can be regarded as a Brabant manuscript. This is important to note for our phonological research.

References

ANROOIJ, W.VAN. 1994. Boek van de wraak Gods. Amsterdam, Querido.

ANROOIJ, W.VAN. 1995. Boendales 'Boec van der wraken': datering en ontstaansgeschiedenis. Queeste. Tijdschrift over middeleeuwse letterkunde in de Nederlanden, 2, pp. 40-52.

ANROOIJ, W.VAN. 2002b. ‘Poenten’ in de Middelnederlandse letterkunde. Een geledingssysteem in het zakelijke en discursieve vertoog. In: Wim van Anrooij e.a. Al t'Antwerpen in die stad : Jan van Boendale en de literaire cultuur van zijn tijd. Amsterdam: Prometheus. 65-80

ANROOIJ, W. VAN et al. 2002a. Literatuur in Antwerpen in de periode ca.1315-1350, een inleiding. In: Al t'Antwerpen in die stad : Jan van Boendale en de literaire cultuur van zijn tijd. Amsterdam: Prometheus. 9-16.

BESAMUSCA, B., R. Sleiderink and G. Warnar. 2009. Ter inleiding. In De boeken van Velthem. Auteur, oeuvre en overlevering, Middeleeuwse studies en bronnen 119, 7-30. ed. B.Besamusca, R.Sleiderink and G. Warnar. Hilversum: Verloren

DESCHAMPS, J. 1972. Middelnederlandse handschriften uit Europese en Amerikaanse bibliotheken. Tweede herziene druk (second revised version). Leiden: Brill.

KESTEMONT, M. Forthcoming. Het gewicht van de auteur; een onderzoek naar stylometrische auteursherkenning in de Middelnederlandse epiek.

KIENHORST, H. 2005. Hoe moet zo’n boek genoemd worden? Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Filologie en Geschiedenis 83: 785-817

KINABLE, D. 1995. Boendales Jans teesteye: een structurele analyse. Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde, 111(4), pp. 323-345.

KINABLE, D. 1998. Facetten van Boendale : literair-historische verkenningen van Jans Teesteye en de Lekenspiegel. Leiden: Dimensie.

REYNAERT, J. 2002. Boendale of 'Antwerpse school'? Over het auteurschap van Melibeus en Dietsche doctrinale. Amsterdam, Prometheus.

SNELLAERT, F.A. 1869. Nederlandsche gedichten uit de veertiende eeuw van Jan Boendale, Hein van Aken en anderen. Brussel.

Appendix

Cluster of texts that referring to ‘Antwerp’. We assume with Reynaert that these can be attributed to Jan van Boendale. The list was compiled by Van Anrooij (Van Anrooij 2002a,13)

| Brabantsche yeesten, first version | ca.1316 |

| Brabantsche yeesten, second version | 1318 |

| Korte kroniek van Brabant, first version | 1322 |

| Brabantsche yeesten, third version | ca. 1324 |

| Sidrac | 1329 |

| Der leken spiegel | ca. 1325-1330 |

| Korte kroniek van Brabant, second version | 1332/33 |

| Jans teesteye | between 1330-1334 |

| Brabansche yeesten, fourth version | ca. 1335 |

| Van den derden Eduwaert | just after 1340 |

| Melibeus | 1342 |

| Boec exemplaar | before Dietsche doctrinale |

| Dietsche doctrinale | 1345 |

| Boec vander wraken, first version | 1346 |

| Brabansche yeesten, fifth version | ca. 1347 |

| Hoemen ene stat regeren sal | before ca. 1350 |

| Brabantsche yeesten, sixth version | 1351 |

| Boec vander wraken, second version | 1351 |

[1] All those who will see, read or hear this work I greet, I Jan, called clerk, born from Vueren. I’m called Boendale there, and now live in Antwerp where I wrote the letters of the magistrates many a year, so I tell you.

[2] …to the honour of a good man and his power, Jan duke of Brabant who I have been obliged to serve many times. I want to leave this book to him.

[3] …that I would readily give …to my dear lord the duke of Brabant. May God elevate both his soul and his body because all I write here is excellent comfort and advice that the lord of the land is worthy of.

[4] In Antwerp where I live, I made this beautiful book

[5] I heard in Antwerp where I sat